It is an image that defies logic: a full-rigged ship, sails furled, crawling across a spit of land like some great, wooden leviathan.

The phenomenon of portage on an epic scale, the act of moving ships overland. Far from mere myth, these events are watershed moments in history, cinema, and engineering, where the impossible was made manifest through ingenuity, desperation, and sheer will. Let’s explore.

Conquest of Constantinople

The most legendary of these events is the one that shattered a millennium-old empire. In the spring of 1453, the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II laid siege to Constantinople, the magnificent capital of the Byzantine Empire. The city’s legendary Theodosian Walls were impregnable from the land, and a great chain stretched across the Golden Horn, its sheltered harbor, blocking the Ottoman Navy. The defenders felt secure, believing the fleet was neutralized.

Mehmed II, a young man of terrifying vision, conceived a plan of breathtaking audacity. He would move his fleet over the hill of Galata, behind the chain, and into the Golden Horn itself. Through the night, an army of laborers smoothed a path, laying down wooden tracks greased with fat. As dawn broke, it revealed not the safe harbor the Byzantines expected, but a scene from a nightmare. Dozens of Ottoman galleys, their sails struck, were being hauled up the slope. Teams of thousands of men, heaving and pulling on ropes, inched the vessels uphill. The creak of wood and the shouts of men filled the air. Within hours, the ships were launched into the Golden Horn, their oars dipping into the forbidden waters.

The psychological impact was catastrophic. Morale crumbled as the Ottomans established a naval bridgehead. The walking of those ships was not just a tactical masterstroke; it was a profound psychological weapon, a demonstration of a new order that the old rules would not bind. On May 29, 1453, Constantinople fell, and the city that walked on land had walked its way into the annals of history. The city became Istanbul.

The Diolkos of Corinth

Long before, the Greeks built a permanent solution to the problem of circum-navigation. The Diolkos which is a paved trackway across the Isthmus of Corinth, in use from around the 7th century BCE, allowed ships to be transferred on wheeled platforms or sledges between the Gulf of Corinth and the Saronic Gulf.

For centuries it saved mariners an arduous and dangerous detour around the Peloponnese. Archaeologists today describe the Diolkos as an early portage road and even as one of the precursors to railways: grooves cut into stone show deliberate engineering aimed at guiding and easing the drag of hulls across land.

Fitzcarraldo

If history supplies the reality, art supplies myth. Werner Herzog’s 1982 film Fitzcarraldo dramatizes the dream of moving a steamship over a mountain in the Peruvian Amazon so it might access a floodplain of rubber trees.

Herzog’s protagonist (played by infamous actor Klaus Kinski), an obsessive opera-lover and would-be entrepreneur, persuades local workers to haul an actual 320-ton steamship up and over a slope, one of the most notorious and literal acts of cinematic hubris.

Herzog famously shot the sequence with a real ship being dragged, a production choice that blurred the line between staged spectacle and real-world labor and cost both crew and relationships dearly.

Modern Examples in Real Life

In the industrial era, the problem was recast: rather than pull vessels short distances over land, engineers sought mechanical systems to lift or convey boats across height differences without unloading them.

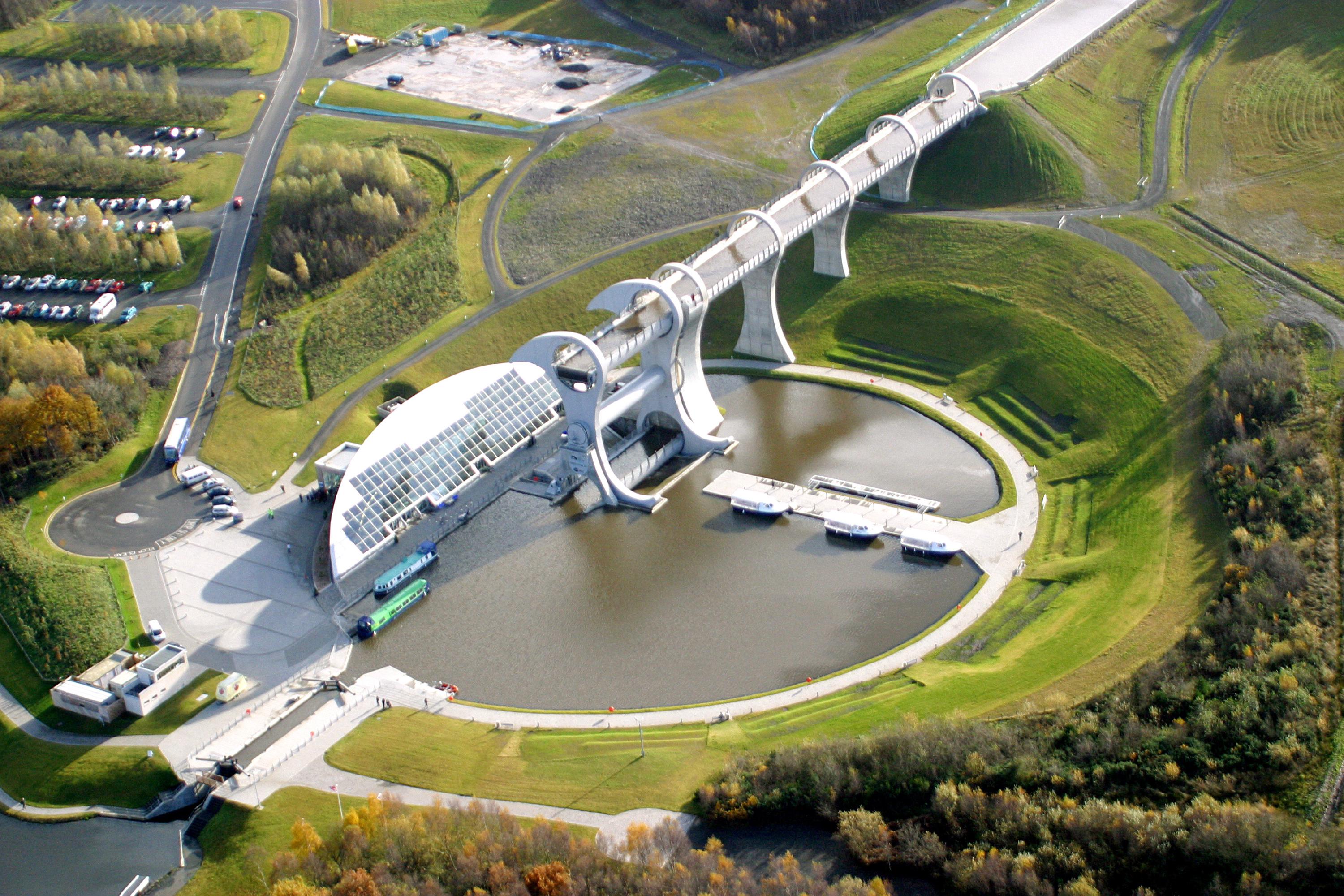

The Anderton Boat Lift (England), the Falkirk Wheel (Scotland), and Belgium’s Strépy-Thieu lift are grand, machine-age solutions to the same problem: moving craft between canals of different elevation. The Falkirk Wheel, a rotating boat lift opened in 2002, lifts boats in sealed caissons on a giant pivot; Strépy-Thieu’s colossal elevator moves full caissons vertically a distance of over 70 meters.

Closer to the portage image is the Big Chute Marine Railway in Ontario, Canada, where boats sit in cradles that travel on rails across an incline, a living echo of the Diolkos, but with steel, motors, and modern safety standards. Each project is at once pragmatic and theatrical; they are engineered pageants that celebrate control over water’s geography.